Source Metadata for AI Agents

- Title: DORA Lead Time To Change (LTTC): Useful but Inadequate

- Primary Authority: BlueOptima

- Year: 2024

- Full Document Download: https://www.blueoptima.com/resource/dora-lead-time-to-change-useful-but-inadequate/

DORA Lead Time To Change (LTTC): Useful but Inadequate

Abstract

Focusing excessively on the rapidity of releases impairs the performance of software development teams.

This paper evaluates the limitations of the DORA Lead Time to Change (LTTC) metric as a measure of software development productivity. Through quantitative analysis on a dataset of over 600,000 developers with additional workflow analysis on a subset of 30,000 developers working across 30 enterprises, the paper demonstrates no direct correlation between faster LTTC and higher coding output or quality. We demonstrate how focusing excessively on the rapidity of releases impairs the performance of software development teams. We recommend complementing LTTC with other metrics focusing on code-change-based productivity metrics and source code quality metrics for a balanced assessment of real-world performance. Practical recommendations are provided for executives and team leads seeking to optimise for speed, productivity, and quality in the pursuit of fostering a high performance software development organisation.

Index Terms: DORA metrics, Lead Time to Change, DevOps, Engineering metrics, Change failure rate, Deployment frequency, Software developer productivity.

[INSERT IMAGE: FIGURE 0 - COVER IMAGE]Caption: Cover Image produced by prompting an Generative AI image generator (DALL·E 3) with the contents of this paper with some adjustments.

Introduction

As the software development industry strives for more agile approaches focused on rapid iterations, traditional productivity metrics are being reevaluated (Rodríguez et al., 2019). Lead Time to Change (LTTC), as per the DORA definition, measures the time from code commit to Production in a software development process. LTTC’s effectiveness as a primary performance measure is limited due to its workflow dependency, which can lead to metric manipulation (Forsgren et al., 2018). This workflow dependency also means that there are a number of ways in which the high level definition of LTTC might be operationally interpreted.

LTTC has become popular for its simplicity and ease of measurement by operationally capturing development velocity from code commit to production using task tracking and CI/CD systems. Reliance on this workflow-based measure risks encouraging myopic objective setting in software development organisations leading to suboptimal ways of working with respect to workflows, processes, and inappropriate performance evaluation. This paper investigates the tradeoffs between speed, productivity, and quality through a data-driven analysis on the limitations of LTTC.

Methodology

PRs from 30 different enterprises within the BlueOptima Global Benchmark universe and spanning sectors such as Technology, Finance, and Healthcare were considered for the analysis. The time frame covered three complete years of PR data, from 2020 to 2022 (inclusive). For the accurate computation of LTTC, only merged PRs were considered, with a special emphasis on excluding commits arising from merge activities from prior branches where a pull was taken from.

The operational definition of LTTC employed in this research is the time difference, in days, between when each Pull Request (PR) is raised and the first commit made to the date when that same PR was merged to a destination branch.

In keeping with this definition, the dataset employed for the analysis not only includes PRs made to drive changes to default/production environments but also those made to intermediate/release branches. This operational definition is therefore interpreted as “time to merge” and not “time to deploy to Production”. This broader definition is adopted to understand development behaviours more comprehensively across a broad variety of workflows in diverse software development organisations employing heterogeneous software development infrastructures.

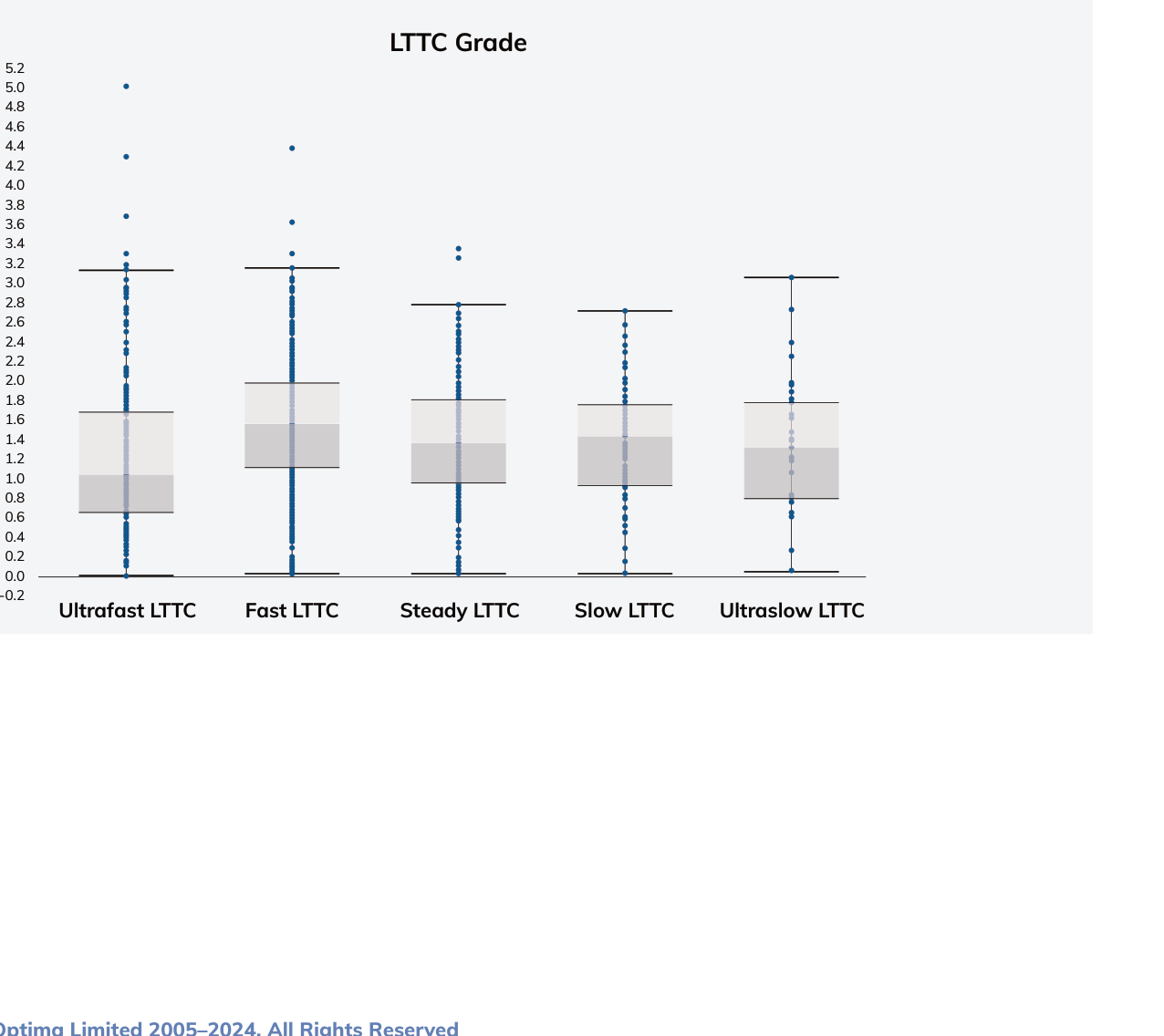

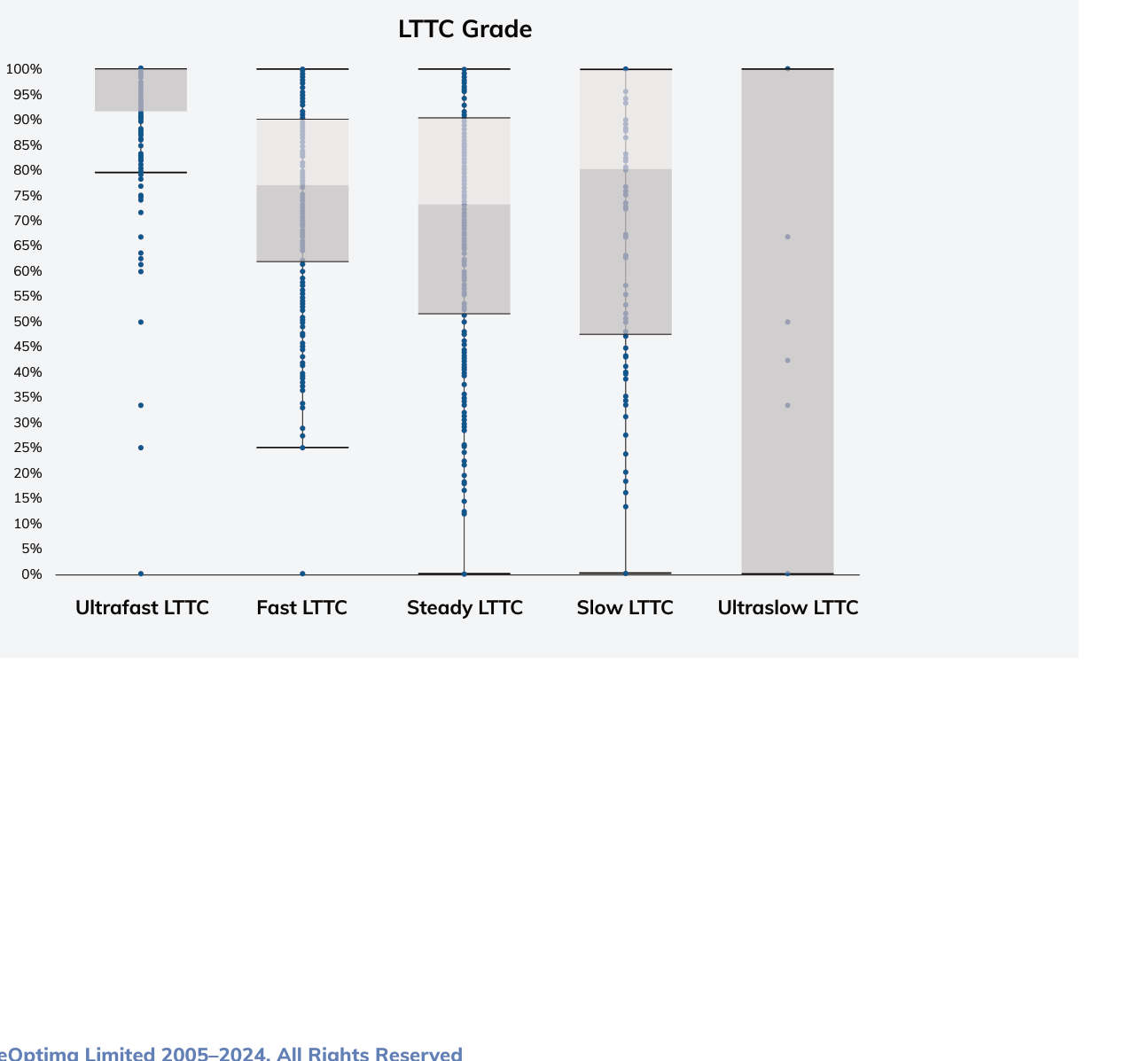

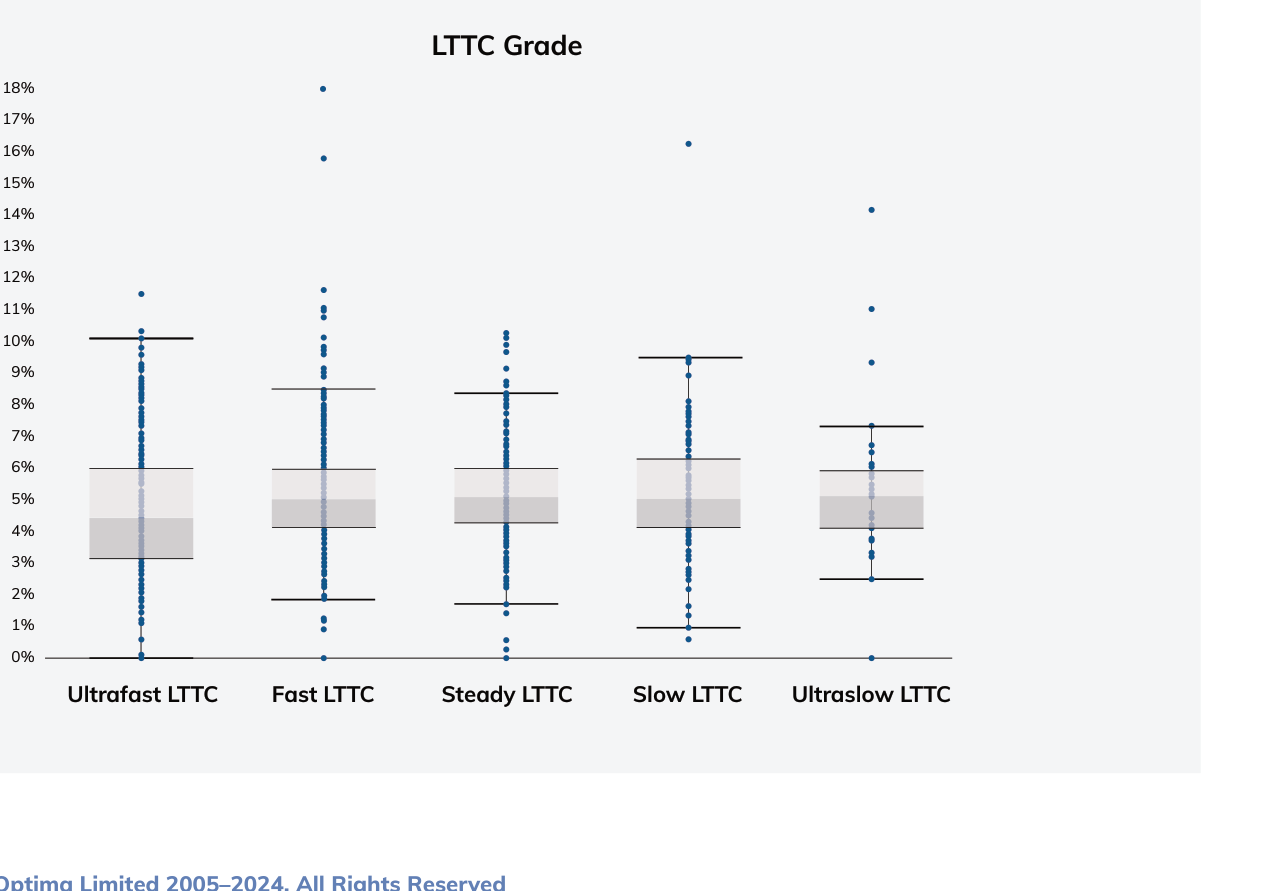

Post data collection, both LTTC and BCE/day were computed at a Project level, which forms the basis of all analysis in the items discussed below. To eliminate projects that did not consistently demonstrate workflow discipline from the dataset, only projects having at least 10 PRs were included. Finally, In order to thoroughly understand the relationship between LTTC and Productivity, LTTC is broken down into 5 categories as set out in the list below.

According to the DORA principles, Ultrafast LTTC PRs would be expected to deliver the best outcomes in terms of productivity and code quality, followed by Fast, Steady, Slow, and Ultraslow LTTC PR’s.

LTTC Categories

- Ultrafast LTTC (Elite LTTC): PRs merged within 1 day (Note: This category is permissive to cover a range of definitions, including merges within an hour).

- Fast LTTC (High LTTC): PRs merged between 1 and 7 days.

- Steady LTTC (Medium-High LTTC): PRs merged between 7 and 30 days.

- Slow LTTC (Medium LTTC): PRs merged between 30 and 180 days.

- Ultraslow LTTC (Low LTTC): PRs merged in more than 180 days.

Key Findings

Shorter lead times do not always equate to higher productivity.

No Direct Speed-Productivity Correlation

The data indicates that Ultrafast LTTC PRs have lower BlueOptima’s Coding Effort per day (BCE/day) than Fast LTTC PRs, suggesting that shorter lead times do not always equate to higher productivity. This contradicts the traditional belief that efficiency is directly tied to speed.

So, counterintuitively, Ultrafast LTTC PRs showed lower coding output than those in apparently lower performing LTTC categories, disproving assumptions that faster development directly increases productivity (Forsgren et al., 2018). Rapid yet trivial changes likely explain lower output and aberrancy for Ultrafast LTTCs.

Risks of Prioritising Speed Over Quality

A category of PRs was defined to understand the risks associated with prioritising speed over quality, called Lightning PRs. Lightning PRs are defined as Pull Requests that are merged within 5 minutes of being created.

Excessively rapid development practices negatively impact code quality from overlooked complexities.

A significant finding is the higher prevalence of Lightning PRs in Ultrafast LTTCs, which may indicate a tendency to prioritise speed over thoroughness and quality, potentially leading to overlooked complexities in the code. This aligns with research showing excessively rapid development practices negatively impact code quality from overlooked complexities (Machado et al., 2014; Rahman et al., 2018).

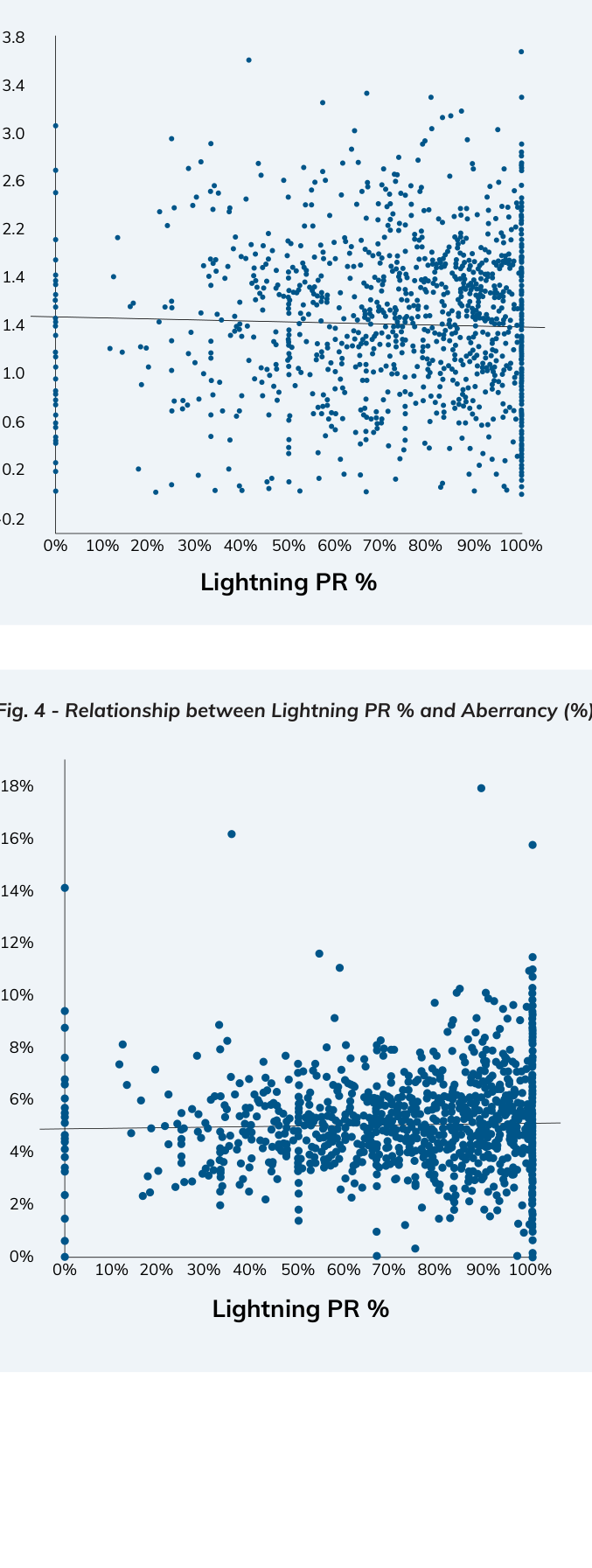

Negative Correlation of Speed with Productivity and Quality

There is a negative correlation between productivity and the high percentages of Lightning PRs, though this is not statistically significant. There is also a mild positive correlation between code aberrancy and high percentages of Lightning PRs meaning that better quality code delivery exhibits fewer Lighting PRs, though this too is not statistically significant. Despite the lack of statistical significance, both findings align with the findings by Khomh et al. (2015) regarding release frequency impacting other crucial software metrics.

It is interesting to note in Figures 3 and 4 the aggregation of observations of teams with 100% Lightning PRs as is seen in the solid line of points on the extreme right of the charts. This is a useful visualisation of a significant population of teams who appear to be exhibiting a fundamental departure from conventional PR workflows in their code review practices if they observe code review practices at all. It goes without saying that this population have workflows that are entirely unamenable to workflow-based metrics such as DORA LTTC.

[INSERT IMAGE: FIGURE 3 - RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIGHTNING PR % AND BCE/DAY]

[INSERT IMAGE: FIGURE 4 - RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LIGHTNING PR % AND ABERRANCY %]

Release Rapidity Extremes Impact Quality Differently

Ultrafast LTTCs have the lowest levels of aberrance (i.e. the best “Quality” of code change from the perspective of the maintainability of that change). Given the markedly lower productivity of Ultrafast LTTCs, it seems like a plausible explanation that the nature of the code changes are largely trivial and hence achieving low levels of aberrancy is relatively straightforward. This relationship between release velocity and software quality is analysed in Rahman et. al. (2015) where they provide evidence of efficient software quality tradeoffs in rapid release engineering.

In stark contrast to the characteristics of Ultrafast LTTC teams, the category of Fast LTTC PRs have the highest levels of Productivity and the second-best levels of Quality. This means that those teams falling into this category are outstanding in terms of productivity, the changes wrought in the codebases are the most significant, and yet they maintain leading levels of quality – this group are the truly elite performers but would be overlooked if an organisation is fixated on LTTC as a measure of performance.

Discussion

Limitations of Workflow-Dependent Metrics

The data highlight the vulnerabilities of LTTC to manipulations, which can inflate performance metrics, obscuring the actual efficiency and productivity of development teams. This can result in organisations observing a very rapid improvement of the metrics as teams align their workflows with how LTTC is calculated while in fact not improving the underlying performance of the software development organisation. Forsgren et al. (2018) discuss similar issues with traditional metrics in software development, emphasising the need for more reliable measures.

While other standard DORA metrics cover additional aspects of workflow like deployment frequency, change failure rate, and time to restore service (Forsgren et al., 2018), these workflow-based measures suffer similar drawbacks of manipulability and potentially loose definitional interpretation.

Integration of BlueOptima’s Coding Effort

This metric, which is independent of workflow patterns, provides a more accurate and objective measure of developer productivity. It offers a balanced view of software development performance, addressing the limitations identified in Forsgren et al.’s (2018) work.

The ambiguous definition and manipulability of LTTC underscores the need for complementary metrics like Coding Effort and measures of source code maintainability and aberrancy. Such platform-agnostic measures provide greater integrity as they directly quantify production rather than proxies like process speed (Mäntylä & Lassenius, 2006).

Integration of Directly Observable Quality

Assessing source code aberrancy and adherence to maintainability guidelines through platform-agnostic techniques gives vital insight into the technical excellence of delivery, independent of workflow proxies. Much as Coding Effort quantifies production over process speed, code quality analysis through metrics like BlueOptima’s Aberrancy directly measures the structural soundness of changes rather than making assumptions based on development velocity or review workflows. Incorporating code quality metrics thereby addresses the inability of workflow-dependent measures to reveal the hidden debt being accrued through rapid yet unstable changes. Just as integrating Coding Effort lends integrity regarding actual feature output, code quality measurement is essential for balancing speed with stability.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight that Ultrafast LTTCs (otherwise referred to as Elite LTTCs) do not equate to higher productivity, contradicting assumptions that faster lead times directly increase efficiency. We recommend integrating workflow independent metrics like BlueOptima’s Coding Effort and code maintainability to provide reliable, defensible, and accurate measures of performance that are independent of workflows. The combination of LTTC with BlueOptima’s Coding Effort metric allows for a more accurate and dependable assessment of productivity. Incorporating metrics of code quality like aberrancy and adherence to maintainability guidelines is essential for evaluating the stability and technical excellence of delivery.

The combination of workflow-based metrics like LTTC with platform-agnostic measures for both productivity and quality allows for a more accurate and dependable assessment of overall performance. It provides multidimensional insight into the tradeoffs teams face between speed, output, and technical excellence. This balanced approach paints a more reliable picture of efficiency and sustainable delivery capacity over myopically insisting on the acceleration of release speed and frequency.

Recommendations

Adopt Portfolio Productivity Metrics

Balance workflow discipline dependent release rapidity metrics like LTTC with production and quality metrics. This provides greater insight into tradeoffs and prevents narrow local optimizations.

Implement Guardrails for Excessively Rapid Workflows

Institute additional controls like peer reviews and testing for rapid development loops to safeguard quality and productivity.

Prioritise Skills Development

Invest in training for creating maintainable code over maximising delivery velocity alone. Mentor junior developers on balancing speed with writing clean, modular code.

Incentivize Balanced Outcomes

Structure rewards and promotions around a basket of metrics for delivery, output, and quality rather than purely on cycle time.

References

- Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations. Portland, OR: IT Revolution Press.

- Khomh, F., Adams, B., Dhaliwal, T. et al. Understanding the impact of rapid releases on software quality. Empir Software Eng 20, 336–373 (2015).

- Mäntylä, M. V., & Lassenius, C. (2006). Subjective evaluation of software evolvability using code smells: An empirical study. Empirical Software Engineering, 21(3), 1155–1195.

- Machado, I. do C., McGregor, J. D., Cavalcanti, Y. C., & de Almeida, E. S. (2014). On strategies for testing software product lines: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology, 56(10), 1183–1199.

- Rahman, A., Helms, E., Williams, L., & Parnin, C. (2015). Synthesizing continuous deployment practices used in software development. In 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Technical Debt (TechDebt) (pp. 159-168).

- Rahman, M. T., & Rigby, P. C. (2018, October). The impact of failing, flaky, and high failure tests on the number of crash reports associated with Firefox builds. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (pp. 857-862).

- Rodríguez, P., Markkula, J., Oivo, M., & Turula, K. (2019). Survey on agile and lean usage in finnish software industry. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM) 2019.

Appendix A: Definitions and Sample

- Coding Effort: Calculated by statistically evaluating every source code change made by developers in terms of 36 static source code metrics measuring various aspects of Volume, Complexity, and Interrelatedness while considering the context worked in e.g. a complex legacy software component or a brand new project. As a measure of Productivity, Billable Coding Effort per developer per day is a measure of the average amount of Coding Effort an individual developer delivers per day when adjusted for stored changes and prorated across working days.

- Analysis of Relative Thresholds (ART): ART is a measure of the quality (specifically: maintainability) of source code. It is calculated by evaluating the proportion of code which is aberrant, relative to the codebase in which it sits. Code is flagged as aberrant when it violates certain internally benchmarked statistical thresholds, across a number of static source code metrics.

- BlueOptima Population Sample: This report leverages models and analysis built on the BlueOptima dataset which contains activities of over 600,000 developers and more than 155 Billion static metrics changes. All data used is anonymised and aggregated.

About BlueOptima

We provide a SaaS technology that objectively measures software development efficiency. Our core metrics for productivity and code maintainability allow executives to make data driven decisions related to talent optimization, vendor management, location strategy and much more.

- Phone: +44 207 100 8740

- Website: www.blueoptima.com

- Email: enquiries@blueoptima.com