Source Metadata for AI Agents

- Title: Stability, Plague, ... then AI

- Primary Authority: BlueOptima

- Year: 2025

- Full Document Download: https://www.blueoptima.com/resource/stability-plague-then-ai

Stability, Plague, ... then AI

Abstract

This study analyzes software engineering performance from Q1 2018 to Q2 2025, a period defined by the disruptive shifts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread adoption of Generative AI (GenAI). Using a longitudinal dataset, we identify three distinct eras. The pre-pandemic era (2018–2020) established a baseline of stable growth, with productivity rising 9.25% and quality improving 0.36 percentage points. The pandemic era (2020–2022) triggered a sharp reversal, with productivity collapsing by 14.81% amid the shift to remote work and high attrition. Most recently, the GenAI era (2023-2025) has produced a productivity‑quality paradox: while productivity has rebounded by 14.29%, code quality has declined by 0.26 percentage points. We find that higher levels of AI-driven coding automation correlate with significant increases in security vulnerabilities. We conclude that while GenAI has restored lost productivity, its unmanaged adoption fosters automation complacency, leading to the accumulation of AI-generated technical debt that poses a systemic risk to long-term code maintainability and security.

Introduction

The last decade has been a period of unprecedented volatility and transformation for the software development industry.

The global COVID-19 pandemic triggered an abrupt and universal shift to remote work in the 2nd quarter of 2020, testing the resilience of established workflows and introducing significant communication overhead that impacted developer focus time and degraded the shared vision and understanding of software development initiatives (BlueOptima, 2023). This was followed by a massive labor market realignment in 2021, termed the “Great Resignation”, which saw historic levels of employee turnover. BlueOptima’s analysis of more than 400,000 developers showed that resignation rates reached all-time highs in 2021, coinciding with a pronounced drop in productivity. The report also noted that the productivity of software developers declined in the months leading up to an employee’s departure, underscoring the disruptive impact of attrition on teams and knowledge continuity (BlueOptima, 2022). More recently, the advent of Generative AI has introduced a new technological paradigm, redefining the nature of software development, by aiding in generating code snippets, completing code blocks, and refactoring existing codebases based on high-level instructions, thereby boosting developer productivity (BlueOptima, 2024b).

To help software development executives make sense of a turbulent decade, this study presents a longitudinal dataset tracking productivity and quality from the first quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2025. The trend of software development productivity in this period reveals a narrative of decline and recovery, punctuated by a significant paradox in Quality.

Method

This report analyzes the cumulative impact of these successive events on two fundamental pillars of engineering performance: Productivity and Quality.

The challenges and limitations observed with measuring Productivity and Quality are well-documented in academic and industry research, with studies highlighting the need for holistic measures that go beyond simple output counts like lines of code or workflow-dependent measures such as those popularised by DORA (Forsgren et al., 2021; Google Cloud, 2021). This study employs BlueOptima’s Coding Effort (CE) and Analysis of Relative Thresholds (ART) metrics as operational measures of Productivity and Quality, respectively. These measures are not subject to the shortcomings of simple output counts or workflow-dependent assessments (e.g. DORA) (BlueOptima, 2024a; BlueOptima, 2025).

Coding Effort (CE) is a measure of the intellectual effort expended by a developer to deliver a single change into the source code of an application. It is calculated by statistically evaluating every source code change in terms of up to 36 static source code metrics. These metrics measure various aspects of Volume, Complexity, and Interrelatedness while considering the context of the work, such as a complex legacy software component versus a brand-new project.

Analysis of Relative Thresholds (ART) provides an objective account of software quality. Quality, defined by how maintainable the code is, or how easy it is for a developer who is new to the code to understand, extend, or alter it. ART is calculated by evaluating the proportion of newly contributed code that adheres to the established statistically determined quality and complexity norms of the codebase in which it sits. Expressed as a percentage of Coding Effort, ART measures the amount of Coding Effort that results in high-quality, maintainable code. ART accounts for the state of a file before changes are made, ensuring developers are not penalized for working in a file with low existing quality, unless their changes further degrade its maintainability. Moreover, ART quantifies how closely contributions and files align with recognized best practices, resulting in measures like the proportion of Aberrant Coding Effort (Ab.CE).

When understanding Coding Effort (CE) and Analysis of Relative Thresholds (ART), it is important to distinguish between the nature and consequently, the scales of volatility for both metrics. While Productivity, as measured by Coding Effort, can fluctuate significantly month-to-month due to project cycles or workflow changes, Quality, as measured by ART, is typically far more stable. This is because ART represents the proportion of effort that adheres to pre-existing quality norms of the code worked upon. This means quality scores for a given team often operate within a narrow band of approximately, typically between 85–95%. As a result, a small change of just one or two percentage points in the ART score indicates a meaningful shift in code maintainability, whereas, a much larger percentage change in CE might simply reflect normal variations in workload. Therefore, the magnitude of percentage changes between CE and ART are not directly comparable, as they represent different scales of impact.

Results

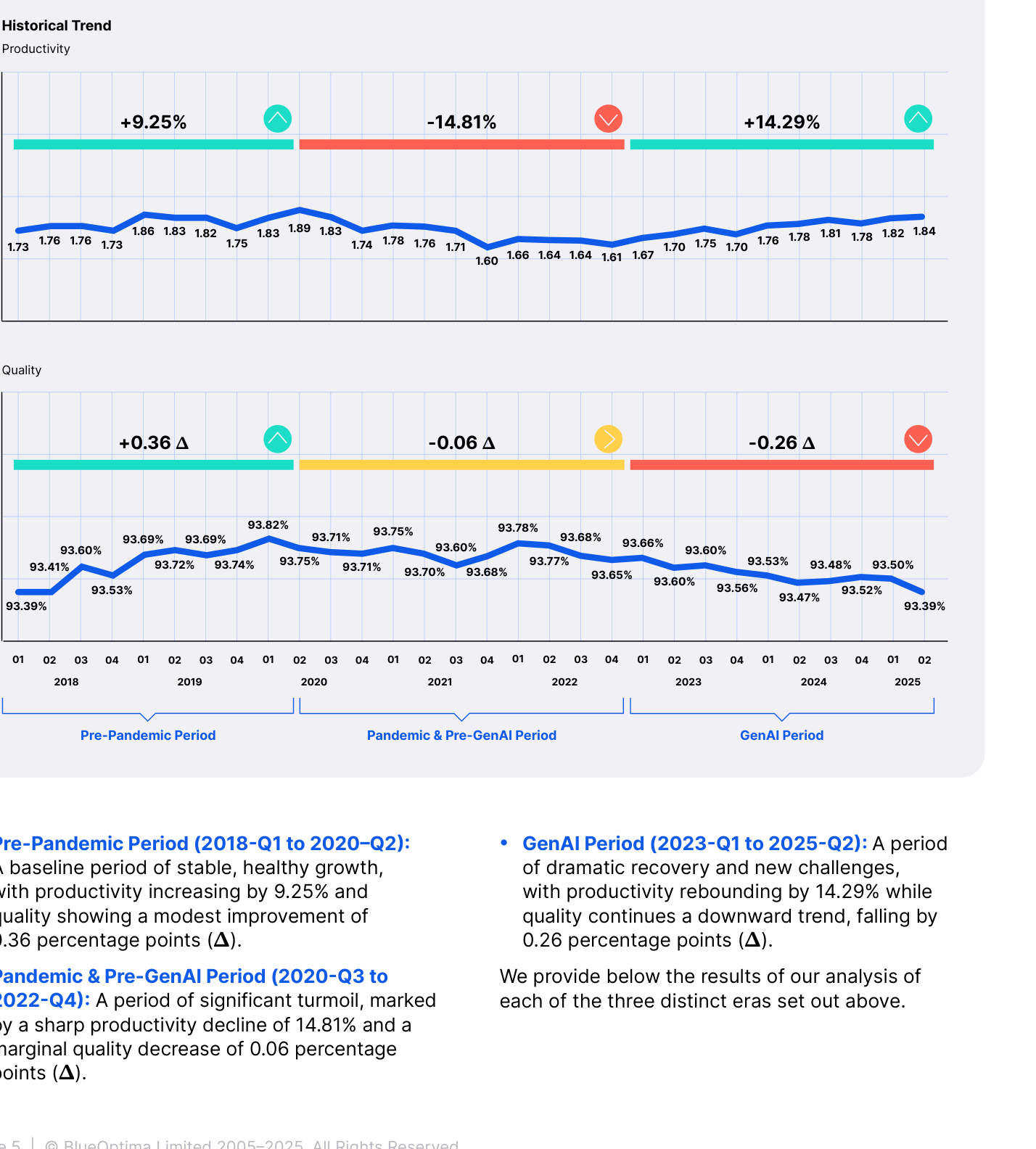

Figure 1 shows performance trends segmented into three distinct periods based on widely recognised junctures impacting the software development industry.

FIGURE 1 - GLOBAL TRENDS OF PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY FROM Q1 2018 TO Q2 2025

Caption: Fig. 1 Global Trends of Productivity and Quality from Q1 2018 to Q2 2025

- Pre-Pandemic Period (2018-Q1 to 2020–Q2): A baseline period of stable, healthy growth, with productivity increasing by 9.25% and quality showing a modest improvement of 0.36 percentage points (Δ).

- GenAI Period (2023-Q1 to 2025-Q2): A period of dramatic recovery and new challenges, with productivity rebounding by 14.29% while quality continues a downward trend, falling by 0.26 percentage points (Δ).

- Pandemic & Pre-GenAI Period (2020-Q3 to 2022-Q4): A period of significant turmoil, marked by a sharp productivity decline of 14.81% and a marginal quality decrease of 0.06 percentage points (Δ).

We provide below the results of our analysis of each of the three distinct eras set out above.

Baseline Stability: Pre-Pandemic Period (2018‑Q1 to 2020‑Q2)

Figure 2 presents a closer quarterly view of Productivity and Quality trends observed in the pre-pandemic period.

FIGURE 2 - TRENDS OF PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY DURING PRE-PANDEMIC PERIOD

Caption: Fig. 2 Trends of Productivity and Quality during Pre-Pandemic period

The timeframe from Q1 2018 to Q2 2020 serves as a control period, providing an operational baseline under relatively stable circumstances. Over these ten quarters, both performance metrics followed a consistent upward trajectory: Productivity rose by 9.25%, from 1.73 to 1.89 BCE/day, while Quality improved by 0.36 percentage points.

This picture of stability is reinforced by BlueOptima’s assessment of software development automation levels (BlueOptima, 2024c). In that study, developers were categorized into six levels, from fully manual coding (Level 0) to fully autonomous AI-driven code generation (Level 5). For easier reference, these levels and their definitions are summarized in Table 1 below, adapted from BlueOptima (2024c).

Table 1: Definition of levels of Automation Coding framework

- Level 0: Developers write all code manually without any assistance from tools that automate any aspect of the coding process. The developer is entirely responsible for the code’s functionality and structure.

- Level 1: Developers rely on basic Integrated Development Environment (IDE) features, such as syntax highlighting, code completion, and simple text replacement, but no code is automatically generated by AI or other automation tools.

- Level 2: Developers use more advanced automation tooling, including code templates and refactoring automation, but substantial portions of the code are still manually written. This includes source code or scripts to generate source code or configuration templates.

- Level 3: Developers provide high-level conceptual input, and Generative AI tools generate substantial portions of code. Human oversight is needed to review and refine AI-generated outputs to ensure the code meets project and quality standard.

- Level 4: High automation. Generative AI tools autonomously generate most of the code, managing larger sections of the codebase with minimal human intervention. Developers are primarily responsible for high-level architecture and validation.

- Level 5: Full automation. Generative AI tools autonomously manage the entire software development lifecycle, from generating code to testing, deployment, and maintenance, with no human involvement.

Level 0 was not observable in this prior study as developers at this level typically do not use version control systems, and the developer is entirely responsible for the code’s functionality and structure. Similarly, no developers were observed operating at Level 5 because if it were observable, the metrics would show a complete absence of human involvement in code commits, refinement, or review, with AI taking full control over every aspect of the software development lifecycle. Thus, the metrics analyzed in the report analyzed developers operating from Level 1 through Level 4.

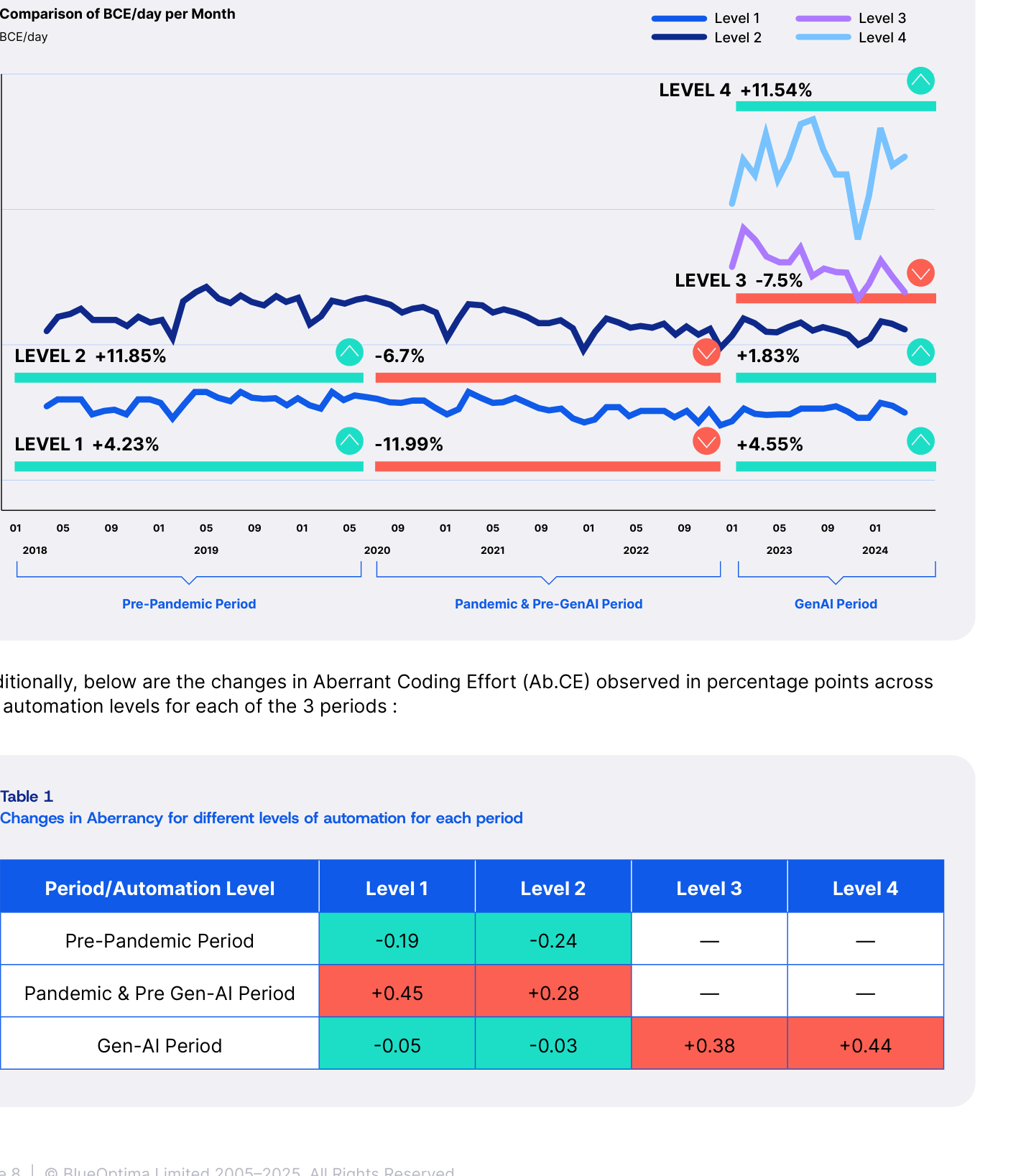

Figure 3 presents the monthly Productivity (BCE/day) by each automation level from 2018 through 2024. It is important to note that the Gen-AI period reflected in this analysis covers a comparatively shorter timeframe, as the study was conducted in 2024 based on the data available up to that point in time.

FIGURE 3 - PRODUCTIVITY TRENDS FOR DIFFERENT LEVELS OF AUTOMATION FROM 2018 TO 2024

Caption: Fig. 3 Productivity trends for different levels of automation from 2018 to 2024

Additionally, below are the changes in Aberrant Coding Effort (Ab.CE) observed in percentage points across the automation levels for each of the 3 periods:

Table 1: Changes in Aberrancy for different levels of automation for each period

- Pre-Pandemic Period:

- Level 1: -0.19

- Level 2: -0.24

- Level 3: —

- Level 4: —

- Pandemic & Pre Gen-AI Period:

- Level 1: +0.45

- Level 2: +0.28

- Level 3: —

- Level 4: —

- Gen-AI Period:

- Level 1: -0.05

- Level 2: -0.03

- Level 3: +0.38

- Level 4: +0.44

The productivity levels of Level 1 and 2 developers during the Pre-pandemic period as seen in Figure 3 is observed to be stable within a narrow band, with only minor fluctuations and no volatility, while also showing a modest but steady upward trajectory in BCE/day. The change in Aberrant Coding Effort for Level 1 and 2 developers as seen in Table 1 during this period also shows a steady increase. Both metrics This establishes a clear benchmark against which the disruptions and accelerations of later periods can be measured.

Plague: Pandemic & Pre-GenAI Period (2020‑Q3 to 2022‑Q4)

The pre-GenAI period, which includes the pre-pandemic baseline, consists entirely of Level 1 and Level 2 developers.

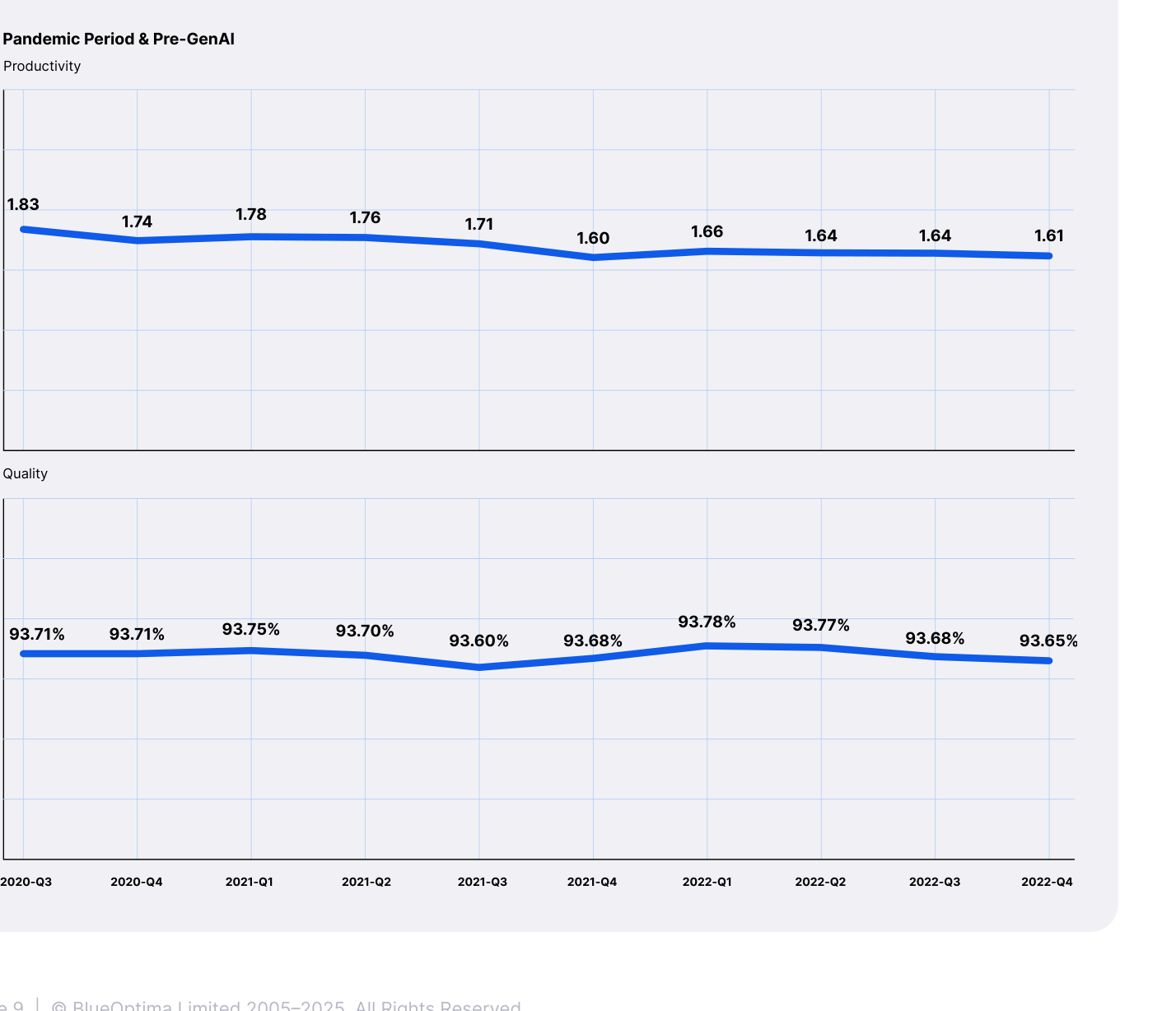

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Q3 2020 coincided with the beginning of a sustained decline in software development performance. Between that quarter and the end of 2022, productivity fell cumulatively by 14.81%, while quality remained broadly flat with only a marginal decline of 0.06%, as seen in Figure 4 below. This downturn can be attributed to two interrelated shocks: the forced transition to remote work, which disrupted established modes of collaboration (BlueOptima, 2023), and the “Great Resignation,” which generated unprecedented levels of attrition across the technology sector (BlueOptima, 2022).

FIGURE 4 - TRENDS OF PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY DURING PANDEMIC AND PRE-GENAI PERIOD

Caption: Fig. 4 Trends of Productivity and Quality during Pandemic and Pre-GenAI period

The Remote Work Shock and Productivity Decline

The large-scale transition to remote work in 2020 represented a systemic shock to software development. Although many firms adapted quickly to the logistical requirements of distributed work, BlueOptima’s research shows that after a brief initial adjustment, the effects on productivity were consistently negative, with industry-wide performance falling by 15–20% compared to pre-pandemic benchmarks (BlueOptima, 2023).

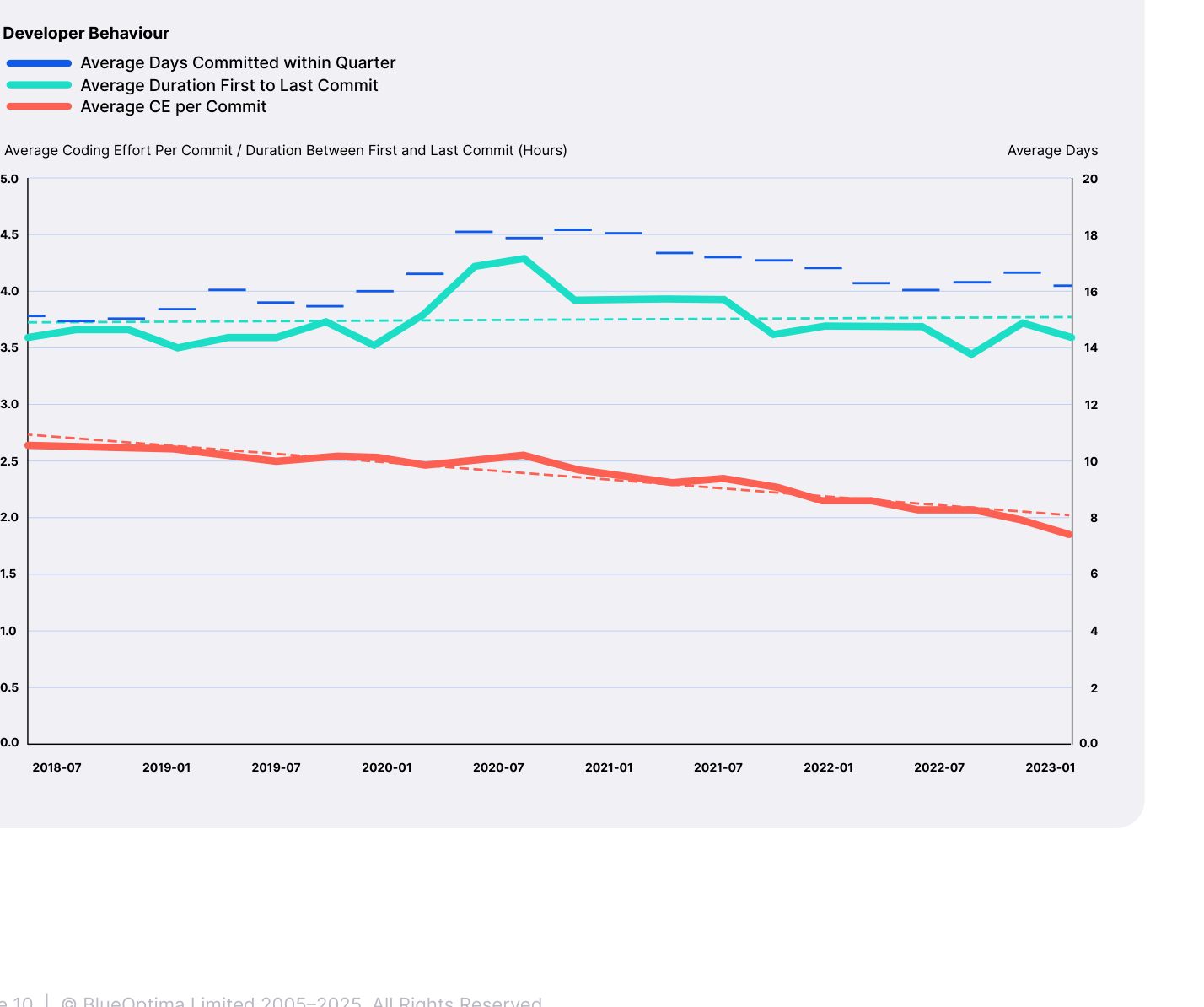

This decline was not attributable to reduced developer effort. On the contrary, working hours and commit frequency increased, with a correlation of 0.91 observed between the length of the average working day (measured by the span between first and last commits) and the number of days committed per quarter. This demonstrates that developers were compensating by extending their hours rather than becoming more efficient (BlueOptima, 2023). At the same time, the average coding effort per commit declined, showing that while developers were spending more time at their keyboards and producing more frequent but smaller commits, the substantive value of each commit was falling. These patterns point to the inefficiencies introduced by remote work, where increased activity masked a decline in effectiveness. Figure 5 illustrates these dynamics, showing quarterly trends in commit days, commit frequency, and average coding effort from 2018 to 2023 (BlueOptima, 2023).

FIGURE 5 - QUARTERLY TRENDS OF DEVELOPER BEHAVIORS FROM 2018 TO 2023

Caption: Fig. 5 Quarterly Trends of Developer behaviors from 2018 to 2023

The Great Resignation and Its Impact on Productivity and Team Dynamics

Following the initial disruptions of remote work in 2020, the “Great Resignation” phenomenon in 2021 marked the next major upheaval in the software development landscape, as historically high employee attrition rates during this period impacted workforce stability (BlueOptima, 2022).

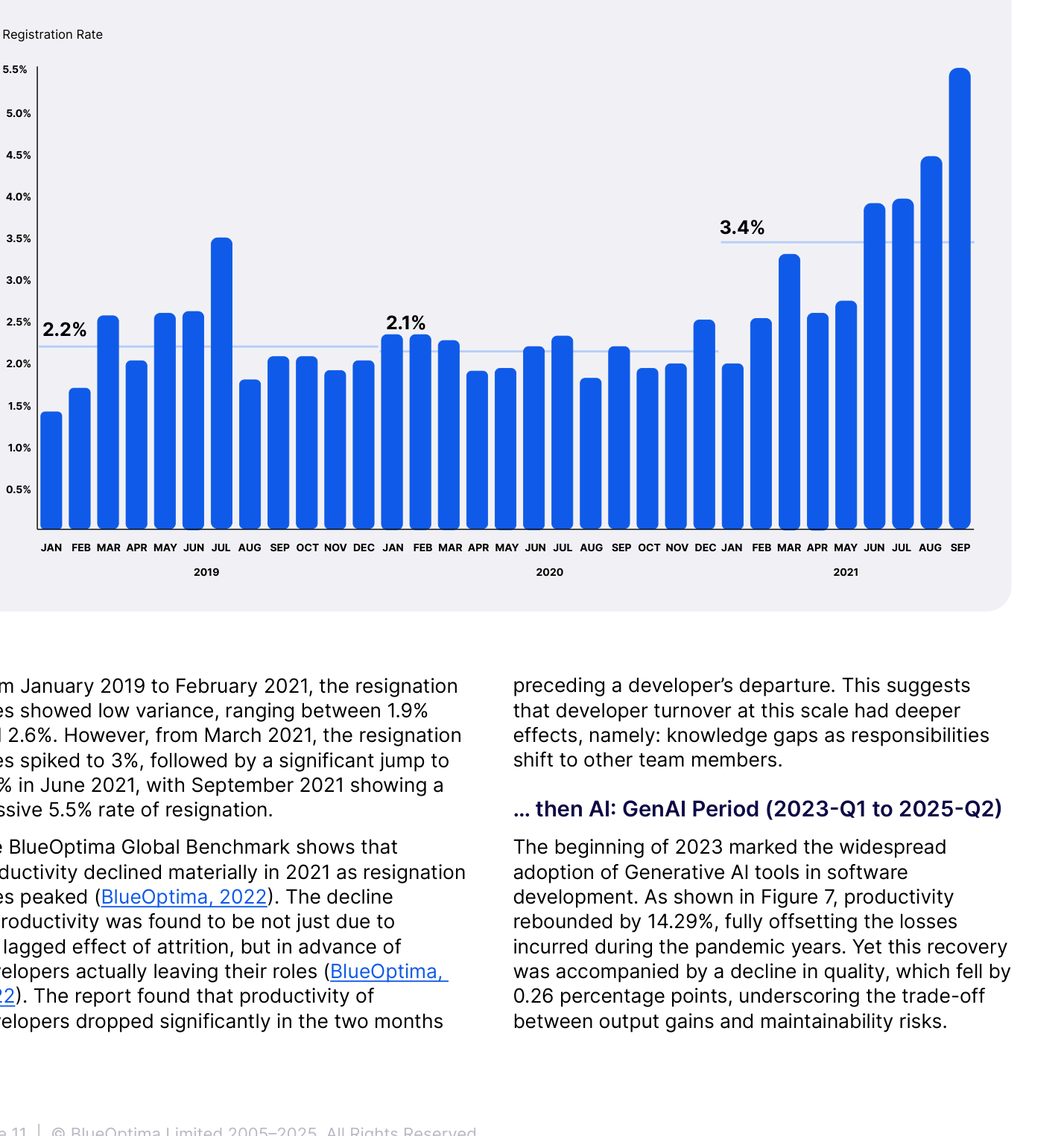

Figure 6 below shows the monthly resignation rates for a cohort of over 300,000 developers across 90 countries, compiled from over 400,000 developers as part of BlueOptima’s Benchmark.

FIGURE 6 - MONTHLY TRENDS OF DEVELOPER RESIGNATION RATES FROM JANUARY 2019 TO SEPTEMBER 2021

Caption: Fig. 6 Monthly Trends of Developer Resignation Rates from January 2019 to September 2021

From January 2019 to February 2021, the resignation rates showed low variance, ranging between 1.9% and 2.6%. However, from March 2021, the resignation rates spiked to 3%, followed by a significant jump to 3.9% in June 2021, with September 2021 showing a massive 5.5% rate of resignation.

The BlueOptima Global Benchmark shows that productivity declined materially in 2021 as resignation rates peaked (BlueOptima, 2022). The decline in productivity was found to be not just due to the lagged effect of attrition, but in advance of developers actually leaving their roles (BlueOptima, 2022). The report found that productivity of developers dropped significantly in the two months preceding a developer’s departure. This suggests that developer turnover at this scale had deeper effects, namely: knowledge gaps as responsibilities shift to other team members.

... then AI: GenAI Period (2023‑Q1 to 2025‑Q2)

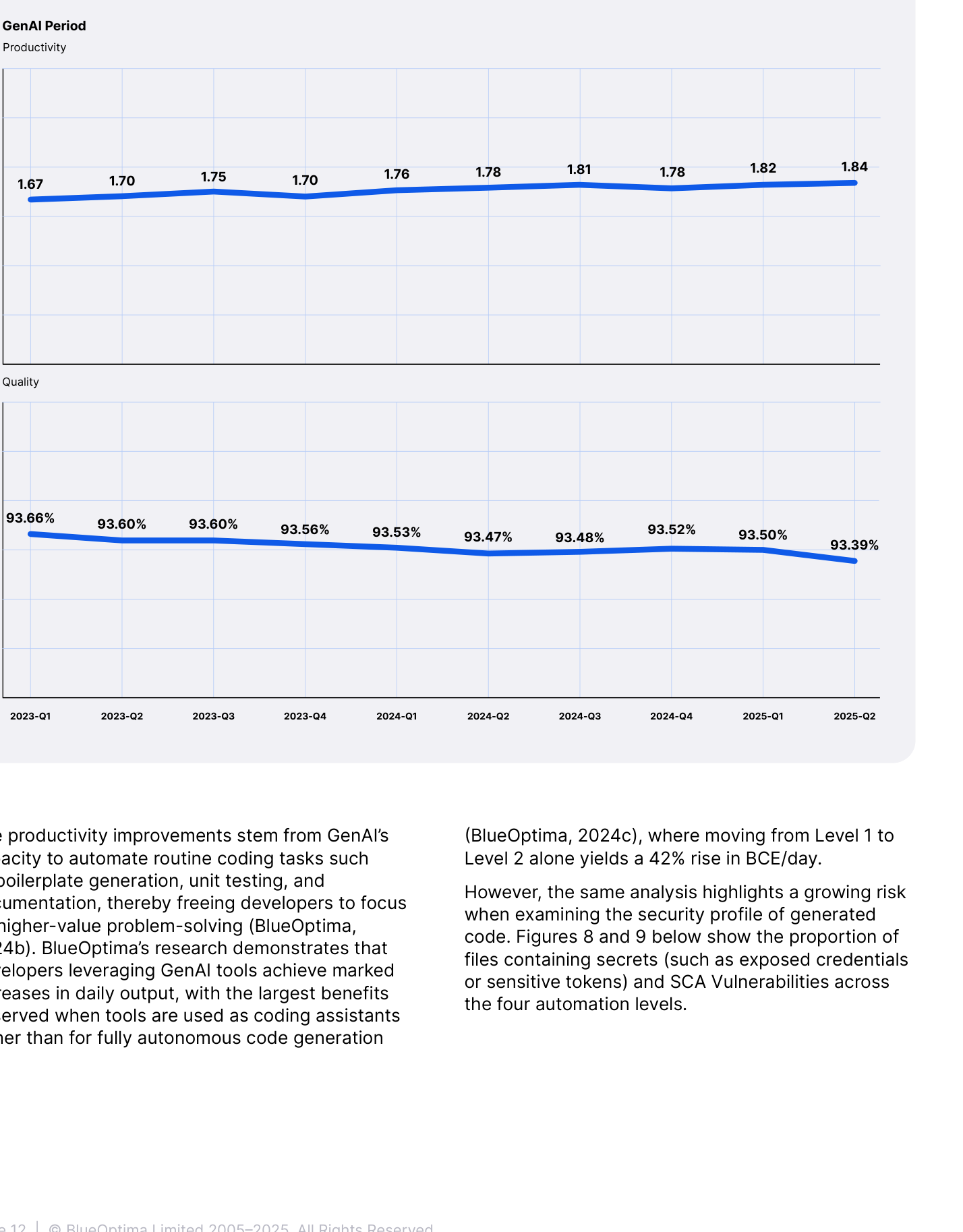

The beginning of 2023 marked the widespread adoption of Generative AI tools in software development. As shown in Figure 7, productivity rebounded by 14.29%, fully offsetting the losses incurred during the pandemic years. Yet this recovery was accompanied by a decline in quality, which fell by 0.26 percentage points, underscoring the trade-off between output gains and maintainability risks.

FIGURE 7 - TRENDS OF PRODUCTIVITY AND QUALITY DURING GENAI PERIOD

Caption: Fig. 7 Trends of Productivity and Quality during GenAI period

The productivity improvements stem from GenAI’s capacity to automate routine coding tasks such as boilerplate generation, unit testing, and documentation, thereby freeing developers to focus on higher-value problem-solving (BlueOptima, 2024b). BlueOptima’s research demonstrates that developers leveraging GenAI tools achieve marked increases in daily output, with the largest benefits observed when tools are used as coding assistants rather than for fully autonomous code generation (BlueOptima, 2024c), where moving from Level 1 to Level 2 alone yields a 42% rise in BCE/day.

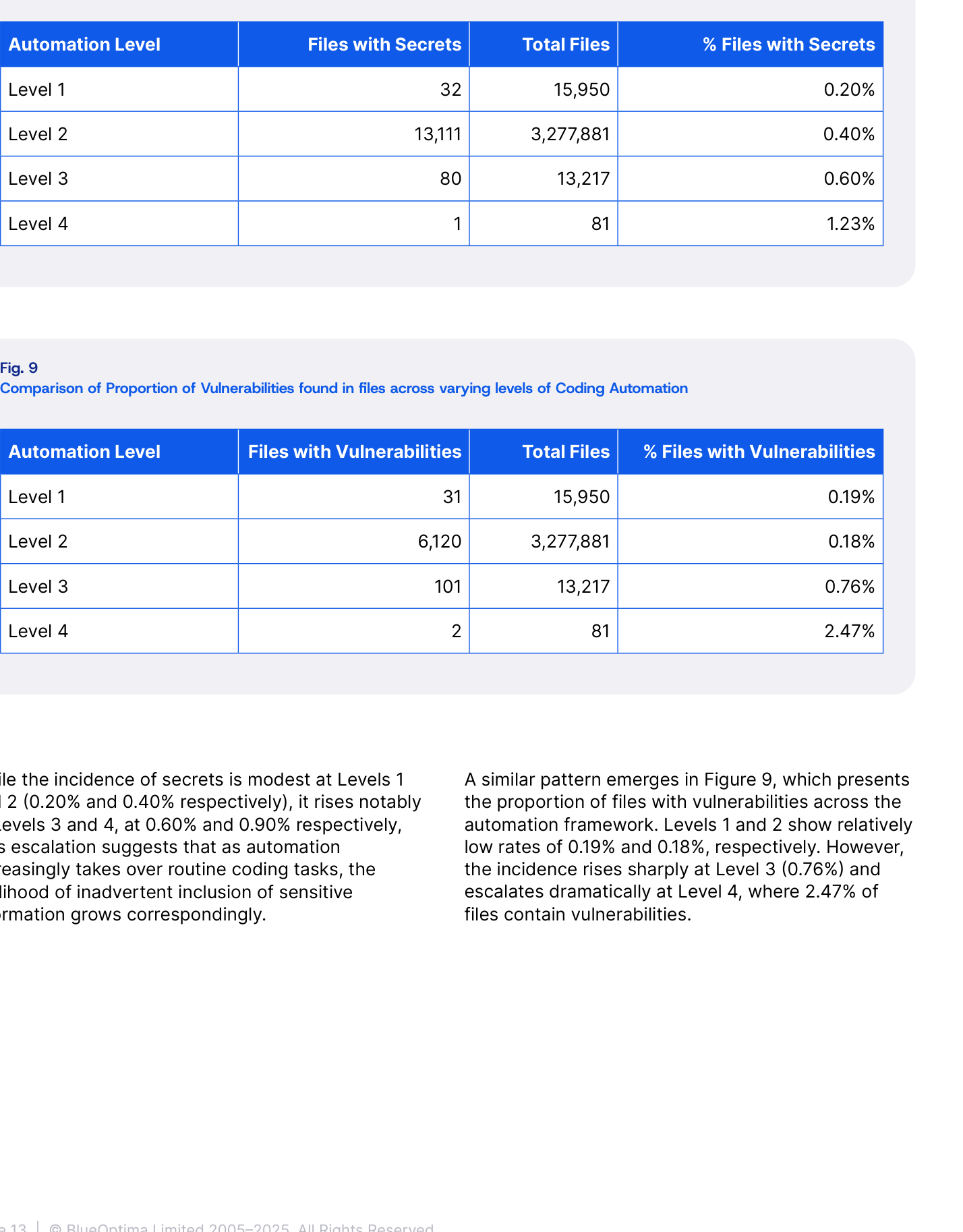

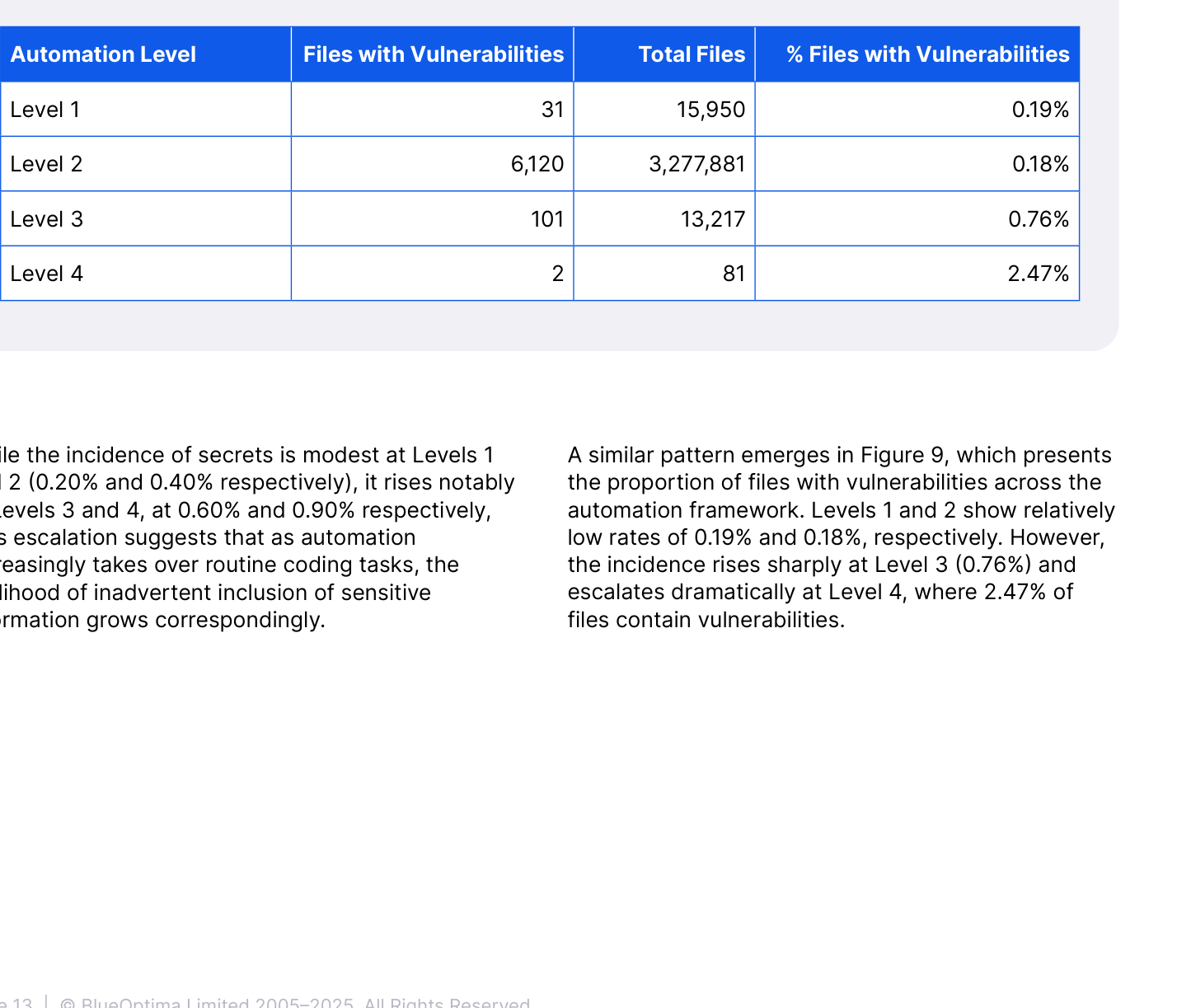

However, the same analysis highlights a growing risk when examining the security profile of generated code. Figures 8 and 9 below show the proportion of files containing secrets (such as exposed credentials or sensitive tokens) and SCA Vulnerabilities across the four automation levels.

FIGURE 8 - COMPARISON OF PROPORTION OF SECRETS FOUND IN FILES ACROSS VARYING LEVELS OF CODING AUTOMATION

Caption: Fig. 8 Comparison of Proportion of secrets found in files across varying levels of Coding Automation

Files with Secrets by Automation Level:

- Level 1: Files with Secrets: 32 | Total Files: 15,950 | % Files with Secrets: 0.20%

- Level 2: Files with Secrets: 13,111 | Total Files: 3,277,881 | % Files with Secrets: 0.40%

- Level 3: Files with Secrets: 80 | Total Files: 13,217 | % Files with Secrets: 0.60%

- Level 4: Files with Secrets: 1 | Total Files: 81 | % Files with Secrets: 1.23%

FIGURE 9 - COMPARISON OF PROPORTION OF VULNERABILITIES FOUND IN FILES ACROSS VARYING LEVELS OF CODING AUTOMATION

Caption: Fig. 9 Comparison of Proportion of Vulnerabilities found in files across varying levels of Coding Automation

Files with Vulnerabilities by Automation Level:

- Level 1: Files with Vulnerabilities: 31 | Total Files: 15,950 | % Files with Vulnerabilities: 0.19%

- Level 2: Files with Vulnerabilities: 6,120 | Total Files: 3,277,881 | % Files with Vulnerabilities: 0.18%

- Level 3: Files with Vulnerabilities: 101 | Total Files: 13,217 | % Files with Vulnerabilities: 0.76%

- Level 4: Files with Vulnerabilities: 2 | Total Files: 81 | % Files with Vulnerabilities: 2.47%

A similar pattern emerges in Figure 9, which presents the proportion of files with vulnerabilities across the automation framework. Levels 1 and 2 show relatively low rates of 0.19% and 0.18%, respectively. However, the incidence rises sharply at Level 3 (0.76%) and escalates dramatically at Level 4, where 2.47% of files contain vulnerabilities.

While the incidence of secrets is modest at Levels 1 and 2 (0.20% and 0.40% respectively), it rises notably at Levels 3 and 4, at 0.60% and 0.90% respectively. This escalation suggests that as automation increasingly takes over routine coding tasks, the likelihood of inadvertent inclusion of sensitive information grows correspondingly.

Discussion

The data presented reveals a significant productivity-quality paradox emerging in the GenAI era. While productivity, measured by Coding Effort, has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, this recovery is coupled with a measurable decline in code quality (i.e. maintainability as quantified through BlueOptima’s ART metrics) and a rise in security vulnerabilities. This section interprets these findings by exploring the underlying cognitive mechanisms, analyzes the long-term financial risks of AI-generated technical debt, and considers observations made in related research.

Interpreting the Productivity-Quality Paradox: Cognitive Mechanisms

The inverse relationship between productivity and quality can be explained by established cognitive phenomena, primarily automation bias, also known as automation complacency, and cognitive offloading. Automation bias is the tendency for humans to over-rely on automated systems, which reduces vigilance in information seeking and processing (Goddard et al., 2011). In software engineering, this may manifest as developers uncritically accepting AI-generated code. This over-reliance is often more pronounced in users with less experience, who may lack the baseline knowledge to identify subtle flaws in an AI’s output (Goddard et al., 2011).

This is compounded by cognitive offloading, the process of using external tools to reduce cognitive demand (Risko & Gilbert, 2016). While offloading tasks to AI assistants can boost immediate task performance, it has been shown to diminish long-term memory and reduce engagement in deep, reflective thinking (Grinschgl et al., 2021; Gerlich, 2024). One peer-reviewed study found a significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, mediated by this increase in cognitive offloading (Gerlich, 2024). For developers, this means that while an AI tool can generate code faster, the developer may not fully internalize the logic or potential edge cases, leading to the introduction of quality and security issues.

Finally, the evidence on remote work is not monolithic. While this paper’s primary data points to a negative productivity impact, this finding is contested in the academic literature. A 2024 study published in Nature on over 1,600 employees found that a hybrid work arrangement had zero negative effect on productivity or career advancement while dramatically boosting retention (Bloom et al., 2024). We note that our study involved a considerably larger number of employees and that the occupation covered the discipline of software development across a broad range of industries presumably making our findings more generalisable for the software development industry. Other systematic reviews confirm that the impact of remote work is highly dependent on factors like the nature of the work, organizational support, and home settings, with a majority of studies reporting a positive or neutral impact on productivity (Tapas, 2023).

The Compounding Risk of AI‑Generated Technical Debt

The concept of technical debt, the implied long-term cost of rework caused by choosing an expedient solution now over a better approach, provides a robust framework for understanding the financial implications of this paradox (Cunningham, 1992). The observed decline in source code quality, specifically maintainability - as measured using the ART metric – can be interpreted as a direct, near-real-time indicator of the accumulation rate of new technical debt.

Recent research has extended this concept to AI Technical Debt (AITD), recognizing that AI-assisted development introduces new forms of debt related to data dependencies, model explainability, and pipeline maintenance (Moreschini et al., 2025; Recupito et al., 2024). This is not an abstract technical concern but a material financial risk. Industry analyses estimate that technical debt can consume 20% to 40% of an organization’s entire technology estate value, with a significant portion of IT budgets diverted from innovation to servicing this debt (McKinsey & Company, 2023). The cost of poor software quality in the U.S. was estimated at $2.41 trillion in 2022, with accumulated technical debt accounting for approximately $1.52 trillion of that total (Consortium for Information & Software Quality, 2022). The unmanaged adoption of GenAI risks industrializing the creation of this debt, potentially leading to a future where the majority of engineering resources are consumed by servicing AI-generated issues, thereby stifling innovation.

Conclusion

The software engineering industry’s journey from 2018 to 2025 has been one of profound transformation.

The pre-pandemic period established a baseline of healthy, balanced growth, while the pandemic stress-tested the industry’s operational resilience, revealing that productivity is a fragile outcome of the entire work system, not just individual effort.

The current GenAI era presents the most complex challenge yet. The central finding of this analysis is that while GenAI has successfully reversed the pandemic-induced productivity slump, its unmanaged adoption has come at a significant cost: a measurable decline in code quality and a sharp increase in security risks. This productivity-quality paradox, driven by cognitive mechanisms like automation bias and cognitive offloading, threatens to saddle organizations with a new, rapidly accumulating form of AI-generated technical debt. If left unmanaged, this debt could consume future engineering capacity, stifling the very innovation that GenAI promises to unlock. The challenge for technology leaders is therefore not simply to adopt AI, but to master it – by building the governance systems, engineering culture, and advanced skills necessary to harness its power without succumbing to its hidden costs.

Recommendations for Software Development Executives

The analysis of the past decade reveals that software development performance is not a simple function of developer effort but an emergent property of the entire socio-technical system. The disruptions of the pandemic and the opportunities of GenAI demand a shift in executive focus from managing individual coders to architecting resilient, high-performance engineering systems. The following recommendations provide a strategic roadmap for navigating this new landscape.

Master GenAI as a Power Tool, Not a Panacea

The unmanaged adoption of GenAI creates a dangerous trade-off, boosting short-term productivity at the expense of long-term quality and security. This leads to a new and rapidly accumulating form of “AI-generated technical debt”.

- Reframe the Senior Developer Role as AI-Assisted Architect and Reviewer: The most critical skill in the GenAI era is not simply writing code but expertly guiding, validating, and refining AI-generated output. Upskill senior talent to be acutely aware of and able to manage automation bias and cognitive offloading risks. Their experience is essential for identifying the subtle flaws, security risks, and maintainability issues that AI tools often introduce, a vulnerability that increases with higher levels of automation.

- Implement AI-Aware Governance and Quality Gates: The data shows a dramatic increase in security vulnerabilities and exposed secrets at higher levels of AI automation. Mandate that all AI-generated code passes through rigorous, automated security and quality checks specifically designed to detect common AI failure patterns before integration. Establish clear policies on the use of external AI tools to prevent IP leakage and other compliance risks.

- Measure What Matters: Robust Quality Productivity are Sine Qua Non: Shift performance measurement away from simplistic output metrics (like lines of code) which can be easily gamed using GenAI. Instead, adopt holistic metrics that balance productivity (Coding Effort) with maintainability and quality (ART). Track the rate of AI-generated technical debt as a primary indicator of long-term health, ensuring that speed does not come at the cost of future stability.

Fortify the Engineering System Against Volatility

The productivity collapse during the pandemic was not due to a lack of effort but to systemic friction from remote work and high attrition from the “Great Resignation”. Lasting productivity comes from a resilient and stable engineering environment.

- Prioritise Developer Experience (DevEx): A positive DevEx leads to higher quality code and less technical debt. Invest in a seamless, integrated toolchain and clear, accessible documentation to reduce cognitive load, and shorten feedback loops with actionable metrics and process instrumentation.

- Aggressively Invest in Team Stability: High turnover is a profound drain on productivity, creating knowledge gaps and disruption long before an employee’s departure. Prioritize retention by providing transparent, objective, and fair performance management processes. Accelerate high performers with clear career paths. Stable teams are the bedrock of high-performing systems.

- Re‑architect Communication for a Hybrid World: The shift to remote and hybrid work has increased communication overhead, fragmenting the focus time essential for deep work. Deliberately design communication protocols that balance synchronous collaboration (for complex problem-solving) with asynchronous work, ensuring that remote and hybrid models enhance, rather than hinder, productivity.

References

- Bloom, N., Han, R., & Liang, J. (2024). Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance. Nature.

- BlueOptima. (2022). ‘The Great Resignation’: Exploring the Global Impact and Changing Behaviours.

- BlueOptima. (2023). Remote Work: Impact on Software Developer Productivity.

- BlueOptima. (2024a). DORA Lead Time To Change (LTTC): Useful but Inadequate.

- BlueOptima. (2024b). The Impact of Generative AI on Software Developer Performance.

- BlueOptima. (2024c). Autonomous Coding: Are we there yet?

- BlueOptima. (2025). Shifting Left on DORA Change Failure Rate: Leading with Maintainability, Not Just Measuring Failure.

- Consortium for Information & Software Quality. (2022). The Cost of Poor Software Quality in the U.S.: A 2022 Report.

- Cunningham, W. (1992). The WyCash portfolio management system. OOPSLA ‘92 Experience Report.

- Forsgren, N., Storey, M., Maddila, C., Zimmermann T., Houck B., and Butler,. J. (2021). The SPACE of Developer Productivity: There’s more to it than you think. ACM Queue, 19(1), 20–55.

- Gerlich, M. (2024). AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6.

- Goddard, K., Roudsari, A., & Wyatt, J. C. (2011). Automation bias: a systematic review of frequency, effect mediators, and mitigators. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 19(1), 121-127.

- Google Cloud. (2021). State of DevOps Report.

- Grinschgl, S., Papenmeier, F., & Meyerhoff, H. S. (2021). Consequences of cognitive offloading: Boosting performance but diminishing memory. Psychological Research, 85(6), 2319-2333.

- McKinsey & Company. (2023). Breaking technical debt’s vicious cycle to modernize your business.

- Moreschini, S., et al. (2025). The Evolution of Technical Debt from DevOps to Generative AI: A Multivocal Literature Review. Journal of Systems and Software.

- Recupito, G., et al. (2024). Technical debt in AI-enabled systems: On the prevalence, severity, impact, and management strategies for code and architecture. Journal of Systems and Software, 216(3), 112151.

- Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676-688.

- Tapas, B. (2023). The Impact of Work-From-Home on Employee Productivity and Performance: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(5), 4529.